LATAKIA, Syria (AP) — Syria’s minority religious and ethnic communities, wary of the country’s new authorities after outbreaks of sectarian violence, were divided in the run-up to the first parliamentary elections after the ouster of Bashar Assad, the former Syrian president.

In the end, some chose to take part in the weekend vote but few managed to break into the country’s new political order.

These tensions played out in Latakia, an idyllic city perched on the Mediterranean coast and a summer tourist destination, which is a former stronghold of the Assad family that ruled the country for 50 years. The city is also the center of the minority Alawite sect — an offshoot of Shiite Islam — to which the Assad family belongs.

After Assad’s ouster in December in a Sunni Islamist-led insurgent offensive, Alawites saw a stark reversal of fortunes. The army, where many of them had enlisted, collapsed and the new authorities purged government agencies of Assad-era employees — particularly Alawites.

In March, pro-Assad armed groups launched attacks on Syria’s new security forces in the coastal region. The clashes spiraled into sectarian revenge attacks in which pro-government fighters killed hundreds of Alawite civilians.

Months later, Latakia’s Alawites say the security situation has stabilized and they mostly coexist with the new authorities, but as election day rolled around they remained fearful of more violence. Their concerns were echoed by other minority groups across the country.

Looking for a new social contract

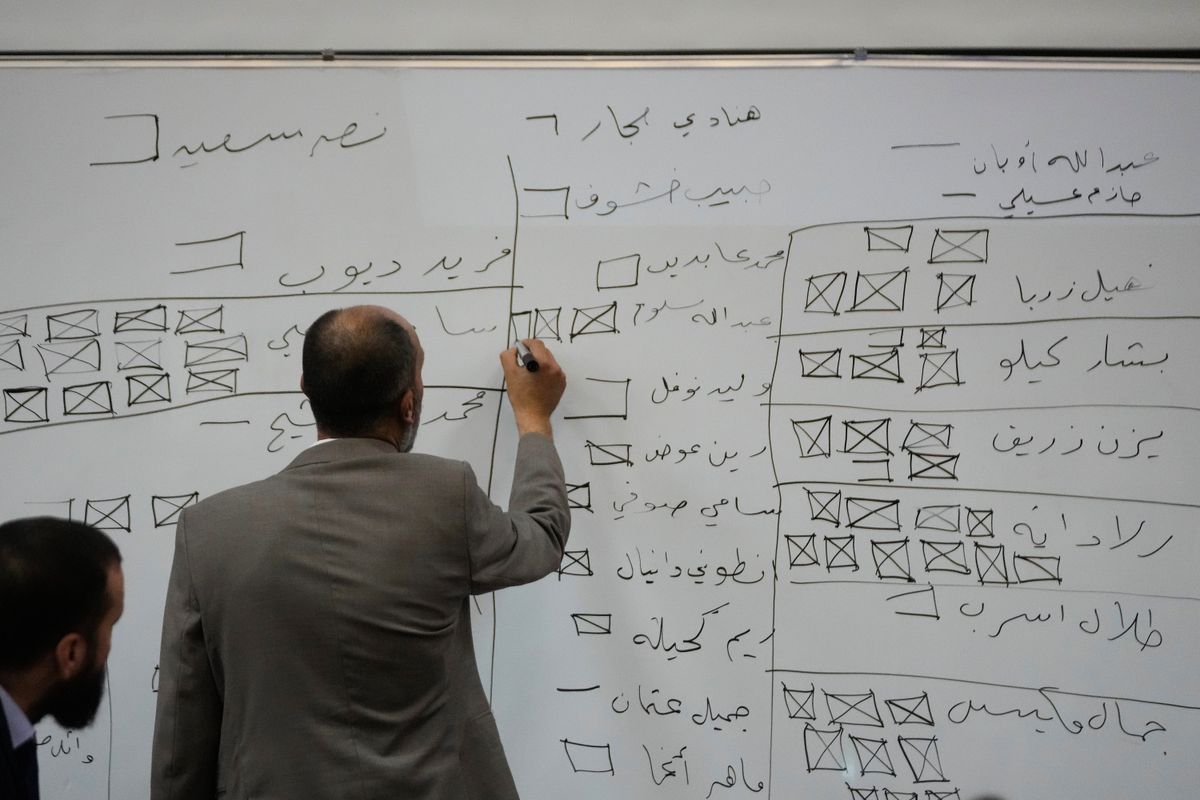

At an auditorium in the Latakia provincial government office, a handful of Alawite candidates were in the crowd Sunday waiting as elections officials read names off of ballots and tallied votes on a board.

One of them, Reem Kahila, a young pharmacist, said it was right to participate in the election. “In the end, we are a component among the components of Syria.”

Nasser Said, 65, who was an opposition activist during the Assad family’s autocratic rule and spent 14 years in prison, also ran — something over which he was “attacked by many people” from his own community, he said.

Others feared for his safety after an Alawite candidate — Haydar Shaheen in neighboring Tartous province — was killed by unidentified gunmen in his home days before the election.

The national elections committee described it as a “treacherous act carried out by remnants of the former regime,” implying that Shaheen was assassinated by pro-Assad militants for running in the elections.

Said said that didn’t bother him. “I want to work with all our brothers in Syria to establish a social contract to build a state,” he said.

When participation is ‘a betrayal’

Adham al-Qaq, one of two candidates from the Druze minority from the Damascus suburb of Jaramana, said his decision to run had alienated some of his neighbors.

“They consider that our presence within the state is a betrayal to them,” said al-Qaq, who, like Said, was previously imprisoned for his opposition to Assad’s rule. He later fled to Egypt, where he opened a publishing house, and only returned to Syria after Assad’s ouster.

In July, clashes broke out between Druze armed groups and local Bedouin clans in the southern province of Sweida, triggered by a series of tit-for-tat kidnappings. Government forces intervened, ostensibly to break up the fighting, but effectively sided with the Bedouins. Hundreds of Druze civilians were killed.

Druze in Sweida are now demanding autonomy, or even secession, from the Syrian state. Amid ongoing tensions, elections in the province were postponed.

Jaramana was not part of the violence, but many residents have close ties to people in Sweida. Some pressed al-Qaq to withdraw his candidacy but he resisted, saying he felt that the Druze “must contribute in one way or another to building the state.”

Participating despite skepticism

Marwan Zaghib, a Christian also running in Jaramana, was openly skeptical of the elections.

Two-thirds of the 210 seats will be filled through votes by electoral colleges in each district, with one-third appointed by Syria’s interim President Ahmad al-Sharaa, who led the offensive that ousted Assad.

The new parliament is supposed to work on a new elections law and prepare the ground for a popular vote. Sunday’s vote was not “something you could call real elections,” Zaghib said.

“But I think it’s better to be at the center of events than not to be,” he added.

Kurdish candidates in the area of Afrin in northern Syria faced a similar dilemma.

The area was seized by Turkish forces and allied Syrian opposition fighters in 2018, following a Turkey-backed military operation that pushed fighters with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces and thousands of Kurdish civilians from the area.

Kurds who remained have complained of discrimination. And though the elections were not held in the SDF-controlled northeast, the vote went forward in Afrin.

Rankin Abdo, a Kurdish doctor, decided to run, hoping to improve conditions for Kurds.

“Boycotting the centers of decision-making and the government doesn’t bring any results,” Abdo said, adding that neither does armed conflict.

“The solution needs to be through dialogue,” she said.

Outside of the polling center, few residents of Latakia had any idea that elections were taking place on Sunday.

Many were skeptical when told about it, like an Alawite owner of a men’s clothing shop, who spoke on condition of anonymity out of fear of retaliation.

He said the security situation in Latakia has improved in recent months, but not entirely. Armed men had come into his shop and insulted him. A neighbor’s daughter had been kidnapped.

When the votes were tallied, the three seats in Latakia city all went to Sunni candidates. The Druze and Christian candidates from Jaramana also failed to secure a seat in their district, which included several other Damascus suburbs.

Only a few women and minorities won seats nationwide.

Nawar Nejmeh, spokesperson for the national committee overseeing the elections, acknowledged that gender representation was a “weak point.” Out of 119 candidates elected, only six were women and 10 were from religious minorities.

Nejmeh said that al-Sharaa could seek to make up for the gaps with his appointments, although he added that the government is against having a “quota” system.

In the Baniyas district of Tartous, the site of some of the worst March massacres, an Alawite candidate won the seat. In Afrin, Abdo and two other Kurds won.

Zaghib, the Christian candidate in Jaramana, said he hopes that al-Sharaa will use his right to appoint the remaining third of the parliament seats to ensure “real participation of all components of our people.”

Jamal Mkaiss, one of the winning candidates in Latakia, pledged to defend “all oppressed people from all sects — Sunni, Alawite, Christian — we are one.”

Meanwhile Said, the Alawite candidate from Latakia, took his loss philosophically and said he still has faith in the process.

“We just were not lucky,” he said. “We are still at the beginning of the road, and I understand that.”

___

Shaheen reported from Jaramana, Syria. Associated Press journalist Omar Albam in Afrin, Syria, contributed to this report.

By ABBY SEWELL and ABDULRAHMAN SHAHEEN

Associated Press