Two days after dozens of journalists left their desks at the Pentagon behind rather than agree to government-imposed rules on how they report about the U.S. military, it’s apparent they haven’t stopped working.

Reporters have relied on sources to break and add nuance to stories about U.S. attacks in the Caribbean on boats suspected of being involved in the drug trade, as well as military leadership in the region.

This comes as many are still navigating how their jobs will change — where will they work? who will talk with them? — brought on by the dispute. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth demanded reporters relinquish their Pentagon workspaces if they didn’t acknowledge rules the journalists say would punish them for reporting on anything beyond what he wants them to say.

The Pentagon has characterized the changes as “common sense” and accused journalists of mischaracterizing them.

“The self-righteous media chose to self-deport from the Pentagon,” Hegseth’s chief spokesman, Sean Parnell, said on social media. “That’s their right — but also their loss. They will not be missed.”

Breaking news on a U.S. attack with survivors

While most press may have departed the Pentagon, it was clear from stories that some sources were still talking.

Reuters broke news Thursday about the first U.S. attack on a boat in the Caribbean where some of the passengers survived. Reporter Phil Stewart, stationed at the Pentagon before leaving Wednesday, sourced it to a “U.S. official” who was not named. President Donald Trump confirmed the attack on Friday as more details emerged, including that two people were taken into U.S. custody.

The New York Times reported on the sudden retirement of U.S. Navy Adm. Alvin Holsey, leader of the U.S. Southern Command, which oversees operations in Central and South America, including use of the military in the administration’s drug-fighting efforts.

Times reporters Eric Schmitt, who covers national security, and Tyler Pager, based in the White House, quoted two unnamed officials saying that Holsey had expressed concerns about the mission and attacks on the boats. The reporters pointed out the unusual nature of a retirement one year into Holsey’s expected three-year command.

Both Hegseth and Holsey released social media statements late Thursday announcing the retirement, with neither addressing reasons for it. A Times spokesman would not comment about whether the newspaper had begun inquiring about Holsey before the retirement was publicly announced.

The Washington Post reported Friday that 15 people had signed the new press policy. They included reporters from conservative outlets the Federalist and the Epoch Times and two from One America News. The others were foreign outlets and freelancers, including six from Turkey. No legacy media outlets agreed.

The newspaper cited a “government document viewed by The Washington Post.” The story was written not by a Pentagon reporter, but by media writer Scott Nover.

One reporter says stories show there are reasons to be hopeful

News outlets that said this week they would leave the Pentagon rather than agree to Hegseth’s rules stressed that it would not stop them from reporting on the military.

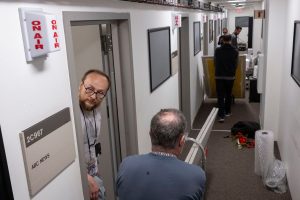

“There are reasons to be hopeful that people can still deliver,” Nancy Youssef, a reporter for The Atlantic, said Friday. After leaving the Pentagon, she’s largely been working at The Atlantic’s Washington office about three miles away.

As much as the access issues raised by the Pentagon exit, reporters expressed concerns that it will make it easier for Hegseth and his team to avoid questions about their actions. For instance, Youssef said she had asked about what weapons had been used in an earlier boat attack, what the legal basis for the action was and the identities of those killed. She received no answer.

Youssef said she also wondered whether journalists who did not sign on to the Pentagon’s rules would be permitted to visit other military sites or be embedded to cover military operations. That remains unclear.

“If you’re in the Navy in charge of the carrier strike group, would you invite a journalist now?” she asked. “Practically speaking, are we allowed to go?”

Even before this past week, Hegseth had taken steps to ban reporters from accessing large parts of the Pentagon without a government escort. He and his team have held only a handful of briefings for journalists.

Two journalists who spoke on background because their outlets would not permit on-the-record interviews said they’re concerned about having fewer opportunities for face-to-face contact with people who work in the Pentagon. Hegseth had begun requiring reporters get an escort to visit press offices for the military’s individual branches, but there were still public information officials near where the reporters worked.

Many Pentagon reporters have developed sources in the building over the course of many years working there. It remains to be seen how many will still answer their calls. “Some people are going to be scared,” one reporter said. “I think that’s inevitable.”

Youssef, however, noted in an article for The Atlantic that mid-level service members had reached out to her, unsolicited, to promise they would keep providing journalists with information. They said they would be doing this not to disobey current leadership but to uphold constitutional values, she wrote.

___

David Bauder writes about the intersection of media and entertainment for the AP. Follow him at http://x.com/dbauder and https://bsky.app/profile/dbauder.bsky.social

By DAVID BAUDER

AP Media Writer