Sometimes, the immune system runs amok and attacks the organ that makes us “us” — the brain. It’s called autoimmune encephalitis but one California man dubbed it his “year of unraveling.”

Christy Morrill went for a bike ride with friends, stopping for lunch — and no one noticed anything wrong until Morrill’s wife asked how the outing went. He’d forgotten. And he would get worse before he got better.

Of all the ways autoimmune diseases can damage the body instead of protecting it, hijacking the brain is one of the most bizarre. Seemingly healthy people can abruptly spiral with confusion, memory loss, seizures, even psychosis. Doctors are getting better at diagnosing it, thanks to discoveries of a growing list of rogue antibodies responsible.

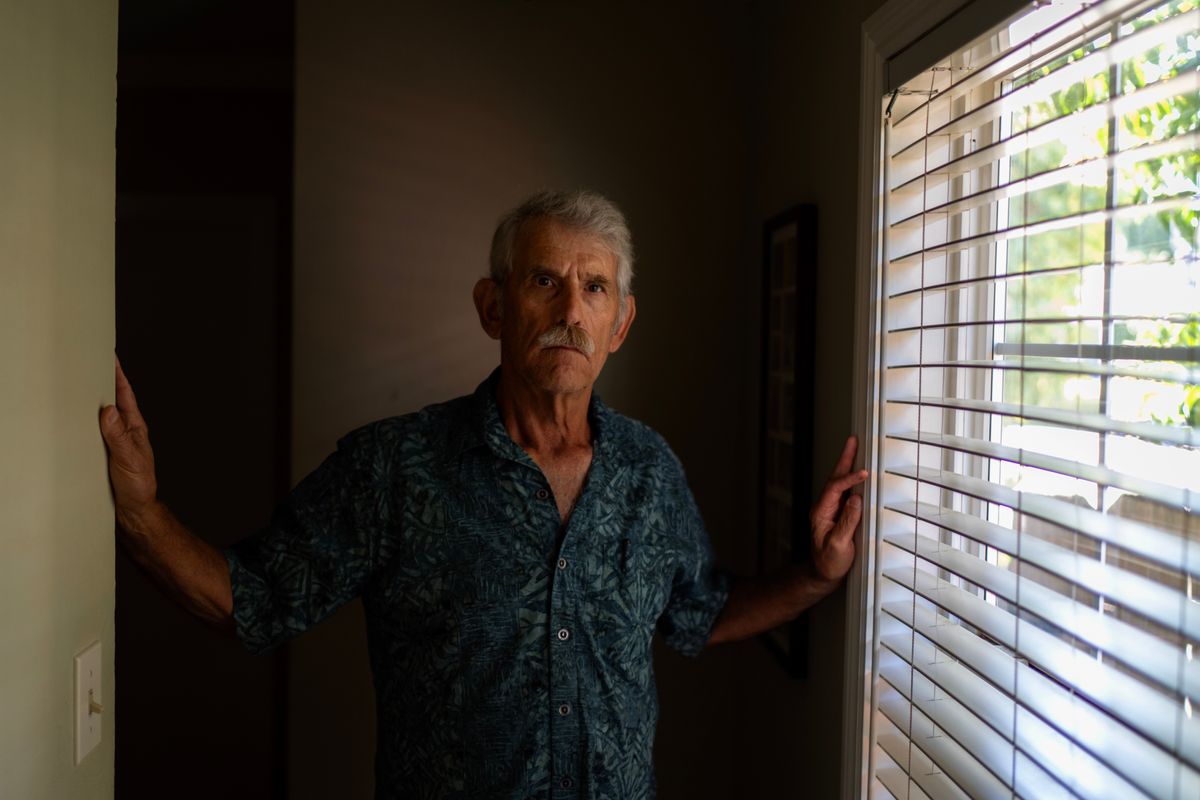

With early diagnosis and treatment, some people can fully recover. But it’s still tricky. And five years after that first symptom, Morrill has resumed normal daily functioning but he grapples with lost decades of “autobiographical” memories.

The 72-year-old literature major can still spout facts and figures learned long ago. He makes new memories every day. But even family photos can’t help him recall pivotal moments in his own life.

“I remember ‘Ulysses’ is published in Paris in 1922 at Sylvia Beach’s bookstore. Why do I remember that, which is of no use to me anymore, and yet I can’t remember my son’s wedding?” Morrill wonders.

Autoimmune encephalitis is an umbrella term that covers a group of brain-inflaming diseases with unwieldy names based on what rogue antibody fuels them.

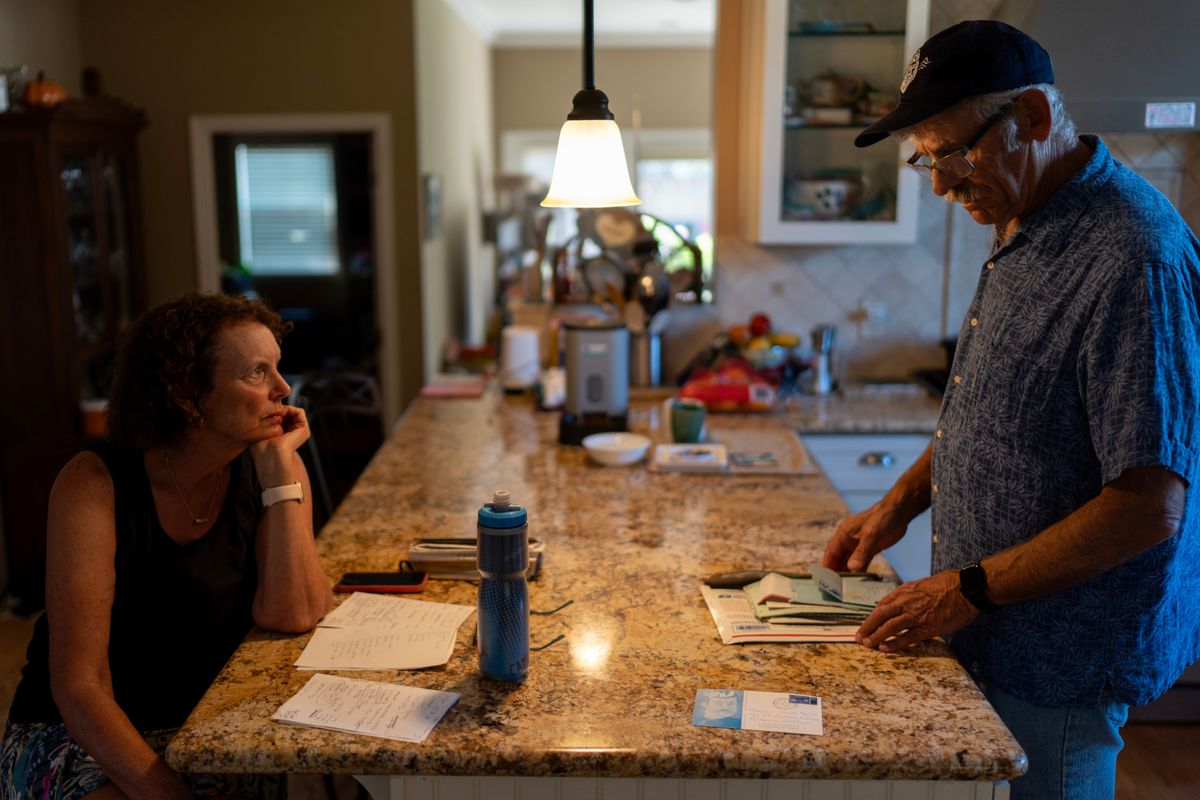

Morrill’s neurologist sent him for specialized testing, trying to get to the bottom of a really unusual type of memory problem. Meanwhile Morrill’s wife, Karen, thought she’d detected subtle seizures — and one finally happened in front of another doctor, helping to spur a spinal tap and diagnosis.

Morrill had what’s called LGI1-antibody encephalitis, a type most common in men over age 50. He started treatments including high-dose steroids to tamp down the brain inflammation, and an antiseizure drug.

He used haiku to make sense of the incomprehensible, writing of being “unhinged” and “fighting to see light” as delusions set in and holes in his memory grew. Months into treatment he finally sensed improvement, wondering if the “meds coursing through me” really were “dousing the fire. Rays of hope?”

Eventually that haiku ended on a high note: “I can sustain hope.”

Today, Morrill still grieves memories lost of family celebrations and travel — but he focuses on making new memories with his family and is back to enjoying the outdoors.

“I’m reentering some real time of fun, joy,” Morrill said. “I wasn’t shooting for that. I just wanted to be alive.”

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

___

This is a documentary photo story curated by AP photo editors.

By DAVID GOLDMAN and LAURAN NEERGAARD

Associated Press