We call them smartphones, small computers that fit in our pockets that can track our location and even pay for things. They can be lost and stolen and they use the same cell service and internet as millions of other devices. Above all people need to trust the information in them is safe from hackers and thieves. But what about law enforcement?

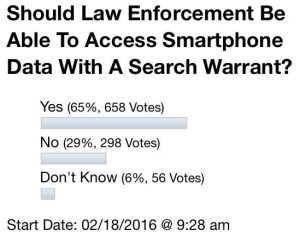

On February 18th an informal myMotherLode poll question asked, “Should Law Enforcement Be Able To Access Smartphone Data With A Search Warrant?” 65 percent said Yes, 29 percent said No, and 6 percent didn’t know.

The Supreme Court of California in January 2011 ruled, in People v. Diaz, that law enforcement officers can conduct a warrant less search of a smartphone after an arrest. The Supreme Court denied hearing the case after learning the California Legislature passed a bill requiring police to obtain a warrant before searching the contents of any “portable electronic devices.” But, one week later, the Governor vetoed the bill, stating that “courts are better suited” to decide this issue of Fourth Amendment law. The Supreme Court decision Riley v. California settled the issue on June 2014: the search-incident-to-arrest doctrine does not apply to cell phones, law enforcement should get a warrant.

The fourth amendment states: The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

How to legally define a warrant for wire tapping and when it is necessary to get a warrant took decades to sort out through the courts, and ultimately special legislation was passed to regulate it. According to a report by the American Bar Association (ABA) Title III of the Omnibus Crime Control Act of 1968 remains the law that governs the federal use of wiretaps– including electronic information. The ABA report notes the federal government may be granted a wiretap order if it can prove there is probable cause for specific crimes: mail fraud, wire fraud, kidnapping, money laundering, bank fraud or computer fraud. When granted a warrant investigators agree to make a reasonable effort to minimize the interception of non-relevant calls and information. Information from a smartphone can be accessed in many ways as detailed in the report “Guidelines on Mobile Device Forensics” by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce here.

Although there are many complexities, the main issue is of privacy versus what is a reasonable and necessary search. A smartphone can contain a lot of information that is not relevant to an investigation as well as information vital to an investigation that only a smartphone can contain. In addition after all recovery methods available are exhausted the FBI decided to bring the maker of iPhones, Apple into the debate.

The FBI and Apple both recently asked congress to settle the question of when and if law enforcement should access citizen’s smartphone data. Microsoft, Google, Twitter, Facebook and Yahoo have said they will support Apple by filing amicus briefs related to a court order. A court approved the FBI requesting Apple unlock a specific iPhone. The iPhone was purchased by the County of San Bernardino and used by Syed Farook, an inspector for the county’s public health department. Farook and his wife, Tashfeen Malik, killed 14 people and wounded over 20 others on December 2nd.

The couple destroyed two personally owned cell phones, crushing them beyond the FBI’s ability to recover information from them, and removing a hard drive from their computer that has not been found despite investigators diving for days in a nearby lake. The iPhone was found in a car after the two were killed in a shoot out with police. According to the Associated Press the county allowed access to the phone’s iCloud information, but Farook stopped backing-up his phone six weeks prior to the terrorist attack.

No one knows the access code to the iPhone, after 10 wrong attempts all the data will be inaccessible. The information is currently inaccessible even to Apple, who has provided default encryption security on its iPhones since October 2014. The feature is great for lost or stole iPhones but also can prevent state and local law enforcement, with warrants for smartphone information, from getting data from a phone. Google’s Android phones are also rolling out similar default full-disk encryption. Legislation to make such encryption illegal has been proposed in New York and California. Logically, if tech companies did comply with with the law, encrypted phones could be bought in other states and other ways to enable encryption will continue to be available.

Apple responded on February 25th that it wants to Vacate the Order compelling it to assist the FBI. According to the AP a New York Magistrate already ruled on February 15th that the FBI cannot make Apple access locked iPhone data related to a routine Brooklyn drug case. Apple noted in that case, as in the California case, the security of its operating system reflects their strong views about consumer security and privacy: “By forcing Apple to write software that would undermine those values, the government seeks to compel Apple’s speech and to force Apple to express the government’s viewpoint on security and privacy instead of its own.”

Apple says, “The government’s demand also violates Apple’s Fifth Amendment right” essentially burdening the company with what to do with the new code to hack a phone after being forced to create it. Apple estimates to unlock the one phone it will take six to ten of its engineers and employees working a minimum of two to four weeks. Apple then has to decide if the code will be used on one phone at a time, or given to the government to use on any phone, both of which Apple says would be bad. Apple estimates the number of phones that different states and governments currently want access to runs in the tens of thousands. Apple or the FBI would have to manage every iPhone search warrant request, essentially creating a forensic lab that handles iPhone evidence. The code and the activity of the lab would become a target for hackers and espionage.

A response from the FBI to Apple is due by March 10th. A hearing is scheduled for March 22nd.