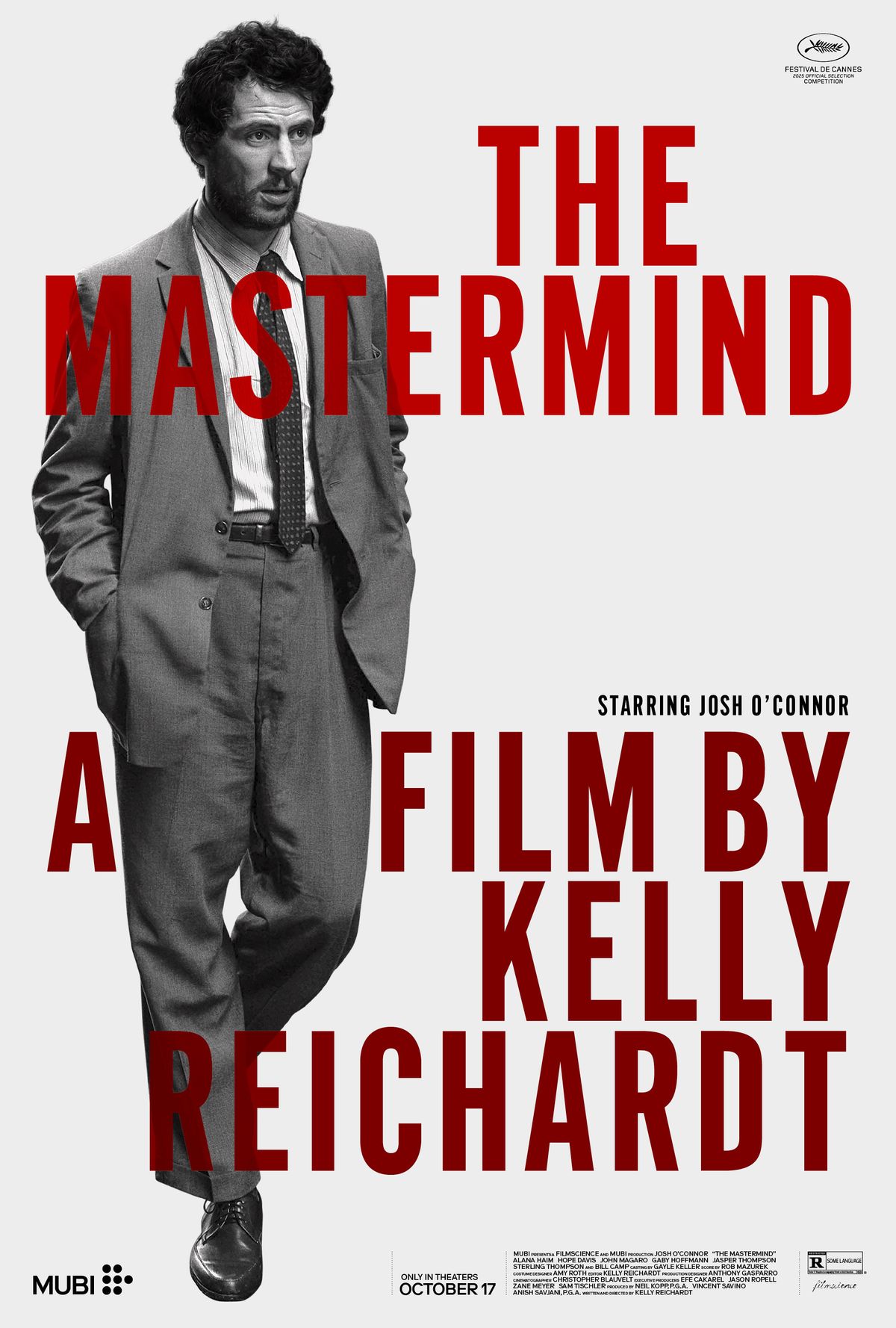

Not far into Kelly Reichardt’s “The Mastermind,” a very different kind of art heist film starring Josh O’Connor, the title’s irony becomes painfully clear.

Because whatever one can say about J.B. Mooney, the mediocre art thief played by O’Connor with a brooding, hangdog sort of anti-energy, it’s obvious what one can’t. This onetime art student, now a family man and unemployed carpenter, is the furthest thing from a mastermind. He is neither clever, quick-thinking nor sensible — qualities one would deem essential to engineering a heist.

But then, as we said, “The Mastermind” is hardly your common heist film. Usually a cinematic heist is spectacular — in its success or its failure. Reichardt has removed all spectacle, telling instead a moody tale of a man who makes a dumb mistake and slowly loses everything, like a tumble down a mountain in slow motion.

“Slow” is the operative term here. Reichardt takes her time with every shot, never in any rush, as she crafts this carefully observed picture of life in early 1970s Massachusetts, tinted in earth tones and costumed to period perfection. This was a time when the now-omnipresent surveillance cameras weren’t around to catch any poor soul who decided to send some guys in to snatch paintings from a gallery in broad daylight and wait right outside in the car, like a dad at school pickup.

We first meet J.B. in the fictional Framingham Museum (Reichardt bases her story very loosely on a 1972 heist elsewhere in Massachusetts), where he’s taken wife Terri (Alana Haim) and two sons on an outing. While the family wanders, J.B. surreptitiously nicks a figurine from a display case, as the security guard naps — an early test of the security system.

At dinner later with J.B.’s parents, his father — a stern local judge (Bill Camp, perfectly cast) wonders aloud why his son is failing on the job front. J.B. says he has something good coming up, and will later hit up his gentler mother (Hope Davis) for funds to finance the project. What’s delicious about this dinner scene, though, is the time Reichardt takes to illustrate a bland ’70s family meal: meat and mashed potatoes, peas, corn on the cob, dinner rolls with butter.

Turns out, J.B. is plotting something nefarious, right in his basement. The simple plan: to steal four paintings — not Old Masters, but works by Arthur Dove, a painter J.B. studied in school. In a meeting at home, he gives his ill-trained thieves their disguise: a pair of L’eggs pantyhose each (remember those pre-sustainability plastic egg boxes?) to stick on their heads.

On heist day, problems arise. At school drop-off, J.B. finds it closed for the day. What’s he gonna do with the kids? You know it’s the ’70s when he lets the young boys loose at a shopping center with some cash for junk food, telling them to be back at the parking lot in a few hours.

The actual crime is remarkably … unremarkable. Reichardt’s observational, almost doc-like style is at its best here. The pantyhose-headed accomplices grab the loot with no thumping soundtrack or hair-raising chases to rev up the energy. After one goes rogue and holds up a teenage girl at gunpoint — there weren’t supposed to be any guns, but he wasn’t listening — they run down a staircase, beat up security guard and jump in the car.

And then the trouble — and the movie — really begins. We realize the story is not about the heist itself, but the spiraling consequences of one man’s unwise decisions, and stunning lack of self-awareness. Has J.B. even figured out how to fence the artwork? The paintings may not even be valuable, muses his dad at dinner, unaware of his son’s involvement. J.B. stashes the works in the silo of a dirty barn somewhere. But what’s next? Well, it doesn’t take long for somebody to squeal.

Soon enough, J.B. is on the run. To his surprise, nobody really wants to see him — not his furious wife, not his friends. He does get a visit from peeved local mobsters. (“Are you guys cops?” he asks.) As he gradually runs out of cash, his options dwindle dramatically. And so do his brain cells; it never occurs to him to change his hair or even shave his beard. Somehow O’Connor has a way of holding onto a tiny iota — tiny, but crucial — of our sympathy.

The supporting cast is perfectly chosen, but it’s a shame Haim isn’t used more — her most poignant scene is on the other side of a phone line, when J.B. is, shockingly, apologizing for upending the family but simultaneously asking her to wire him funds.

Reichardt reminds us at numerous points that her film is set amid the intense social upheaval over the Vietnam War, including vivid street protests. But the truth is that to J.B., social context means nothing. In O’Connor’s unique embodiment of a depressingly mediocre man, our artless art thief seems to care about nothing but survival.

But even there, he doesn’t seem much committed, making careless decisions, the last of which leads to this film’s abrupt — but, in retrospect, satisfying — denouement. And thus ends the tale of our robber without a cause.

“The Mastermind,” a Mubi release, has been rated R by the Motion Picture Association “for some language.“ Running time: 110 minutes. Three stars out of four.

By JOCELYN NOVECK

AP National Writer