This weekend, Mexican American families across the U.S. will gather to honor their ancestors with altars, marigolds and sugar skulls on Dia de los Muertos — the Day of the Dead. In recent years, the celebration has become more commercialized, leaving many in the community wondering how to preserve the centuries-old tradition while evolving to keep it alive.

Day of the Dead is traditionally an intimate family affair, observed with home altars — ofrendas — and visits to the cemetery to decorate graves with flowers and sugar skulls. They bring their deceased loved ones’ favorite foods and hire musicians to perform their favorite songs.

Skeletons are central to the celebrations, symbolizing a return of the bones to the living world. Like seeds planted in soil, the dead disappear temporarily, only to return each year like the annual harvest.

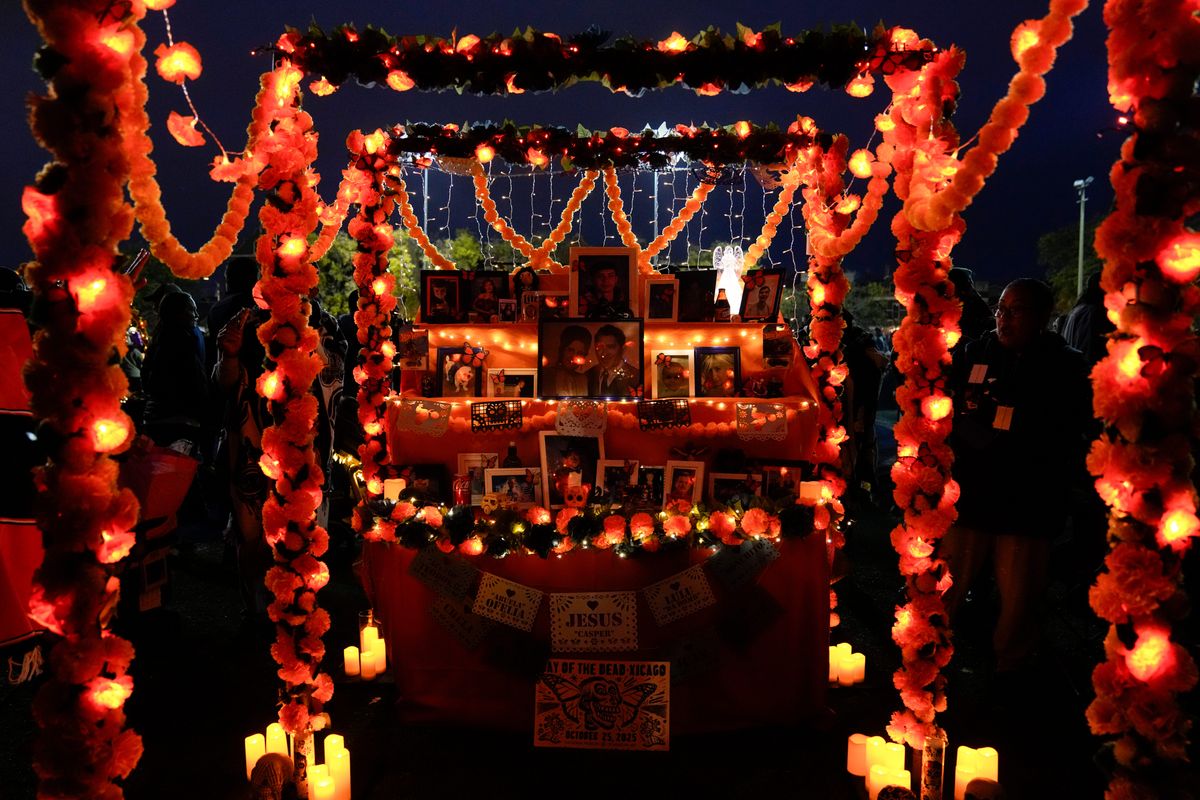

Families place photographs of their ancestors on their ofrendas, which include paper decorations and candles, and are adorned with offerings of items beloved by their loved ones, such as cigars, a bottle of mezcal, or a plate of mole, tortillas and chocolates.

From intimate gatherings to mainstream culture

Day of the Dead celebrations in the U.S. and Mexico continue to evolve.

Cesáreo Moreno, the chief curator and visual director of the National Museum of Mexican Art, said the 2017 release of Disney’s animated movie “Coco” transformed celebrations in northern Mexico and made Day of the Dead more popular and commercialized in the U.S. American cities organize festivals, and Mexico City holds an annual Dia de los Muertos parade.

“Coco” provided a way for people who do not belong to the Mexican American community to learn about the tradition and embrace its beauty, Moreno said. But it also made the celebration more marketable.

“The Mexican American community in the United States celebrates the Day of the Dead as a cultural expression,” Moreno said. “It is a healthy tradition and it actually has an important role in the grieving process. But with ‘Coco,’ that movie really thrust it into mainstream popular culture.”

With its increasing popularity, the Day of the Dead is often confused with Halloween, which has transformed how it is celebrated and people’s understanding of it, Moreno said.

Traditional altars, modernized

In recent years, some in and outside the Mexican American community have built ofrendas devoid of color, leaning towards a more minimalistic aesthetic.

The colorful altars have been part of Mexican and Mesoamerican culture since the Spanish arrived and converted Mexico’s Indigenous tribes to Catholicism. Some families now build altars without the flowers and papel picado — multi-colored lacy wall hangings featuring hearts and skulls — of years gone by.

Moreno said that’s OK, as long as the meaning isn’t lost.

“If people are looking to do something a little bit different, that is fine,” Moreno said. “But if people stop understanding what is at the heart of this tradition, if people start transforming that, that is what I am against.”

Ana Cecy Lerma, a Mexican American living in Texas, suspects the minimalist ofrendas satisfy a desire to create Instagram-worthy content.

“I think you can put what you want in an altar and what connects you to your loved ones,” Lerma said. “But if your reasoning is merely that you like how it looks then I feel that’s losing a bit of the reason as to why we make altars.”

Commercialization raises questions of respect

Sehila Mota Casper, director of Latinos in Heritage Conservation, a nonprofit supporting the preservation of Latinx culture, said American businesses are trying to make money out of Dia de los Muertos as they have Cinco de Mayo, focusing on profit rather than culture. Big chain stores including Target and Wal-Mart now sell create-your-own-ofrenda kits, Mota Casper said.

“It’s beginning to get culturally appropriated by other individuals outside of our diaspora,” she said.

Although not Mexican, Beth McRae has lived in Arizona and California and has always been surrounded by Latino culture. She has created an altar for Day of the Dead since 1994.

She began collecting items related to the celebration in the early 90’s and has amassed a collection of more than 1,000 pieces. And she throws a party to celebrate the day every year.

“This is the coolest celebration because you’re inviting the loved ones that you’ve lost,” McRae said.

“I threw my first Day of the Dead party in San Diego with my very meager collection of items,” she continued, “and it became an annual event.”

McRae said she tries to be respectful by making sure the trinkets she places on her ofrenda are from Mexico, and by focusing on lost loved ones.

“It’s done with respect and love, but it’s an opportunity to raise awareness to people that are not familiar with the culture or are not from the culture,” McRae said.

Salvador Ordorica, a first generation Mexican American who lives in Los Angeles, said traditions must be reinvented so the younger generations want to keep them alive.

“I think it’s okay for traditions to change,” Ordorica said. “It’s a way to really keep that tradition alive as long as the core of the tradition remains in place.”

___

Associated Press reporter Maria Teresa Hernández in Mexico City contributed.

By FERNANDA FIGUEROA

Associated Press