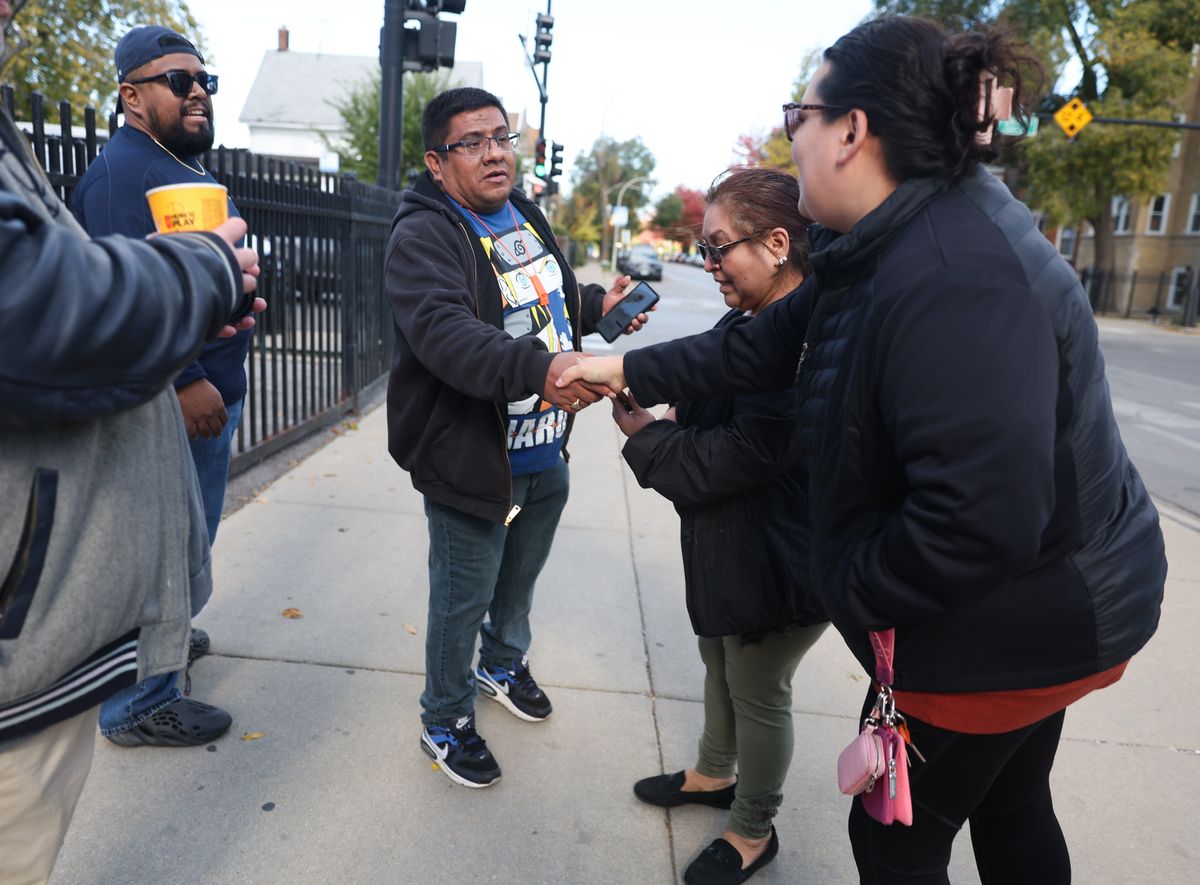

CHICAGO (AP) — Baltazar Enriquez starts most mornings with street patrols, leaving his home in Chicago’s Little Village on foot or by car to find immigration agents that have repeatedly targeted his largely Mexican neighborhood.

Wearing an orange whistle around his neck, the activist broadcasts his plans on Facebook.

“We don’t know if they’re going to come back. All we know is we’ve got to get ready,” he tells thousands of followers. “Give us any tips if you see any suspicious cars.”

Moments later, his phone buzzes.

As an unprecedented immigration crackdown enters a third month, a growing number of Chicago residents are fighting back against what they deem a racist and aggressive overreach of the federal government. The Democratic stronghold’s response has tapped established activists and everyday residents from wealthy suburbs to working class neighborhoods.

They say their efforts — community patrols, rapid responders, school escorts, vendor buyouts, honking horns and blowing whistles — are a uniquely Chicago response that other cities President Donald Trump has targeted for federal intervention want to model.

“The strategy here is to make us afraid. The response from Chicago is a bunch of obscenities and ‘no,’” said Anna Zolkowski Sobor, whose North Side neighborhood saw agents throw tear gas and tackle an elderly man. “We are all Chicagoans who deserve to be here. Leave us alone.”

The sound of resistance

Perhaps the clearest indicator of Chicago’s growing resistance is the sound of whistles.

Enriquez is credited with being among the first to introduce the concept. For months Little Village residents have used them to broadcast the persistent presence of immigration agents.

Furious blasts both warn and attract observers who record video or criticize agents. Arrests, often referred to as kidnappings because many agents cover their faces, draw increasingly agitated crowds. Immigration agents have responded aggressively.

Officers fatally shot one man during a traffic stop, while other agents use tear gas, rubber bullets and physical force. In early November, Chicago police were called to investigate shots fired at agents. No one was injured.

Activists say they discourage violence.

“We don’t have guns. All we have is a whistle,” Enriquez said. “That has become a method that has saved people from being kidnapped and unlawful arrest.”

By October, neighborhoods citywide were hosting so-called “Whistlemania” events to pack the brightly colored devices for distribution through businesses and free book hutches.

“They want that orange whistle,” said Gabe Gonzalez, an activist. “They want to nod to each other in the street and know they are part of this movement.”

Midwestern sensibilities and organizing roots

Even with its 2.7 million people, Chicago residents like to say the nation’s third-largest city operates as a collection of small towns with Midwest sensibilities.

People generally know their neighbors and offer help. Word spreads quickly.

When immigration agents began targeting food vendors, Rick Rosales, enlisted his bicycle advocacy group Cycling x Solidarity. He hosted rides to visit street vendors, buying out their inventory to lower their risk while supporting their business.

Irais Sosa, co-founder of the apparel store Sin Titulo, started a neighbor program with grocery runs and rideshare gift cards for families afraid of venturing out.

“That neighborhood feel and support is part of the core of Chicago,” she said.

Enriquez’s organization, Little Village Community Council, saw its volunteer walking group which escorts children to school, grow from 13 to 32 students.

Many also credit the grassroots nature of the resistance to Chicago’s long history of community and union organizing.

Trump’s “border czar” Tom Homan said Chicago area residents were so familiar with their rights that making arrests during a different operation this year was difficult.

So when hundreds of federal agents arrived in September, activists poured energy into an emergency hotline that dispatches response teams to gather intel, including names of those detained. Volunteers would also circulate videos online, warn of reoccurring license plates or follow agents’ cars while honking horns.

Protests have also cropped up quickly. Recently, high school students have launched walkouts.

Delilah Hernandez, 16, was among dozens from Farragut Career Academy who protested on a school day.She held a sign with the Constitution’s preamble as she walked in Little Village. She knows many people with detained relatives.

“There is so much going on,” she said. “You feel it.”

A difficult environment

More than 3,200 people suspected of violating immigration laws have been arrested during the so-called “ Operation Midway Blitz.” Dozens of U.S. citizens and protesters have been arrested with charges ranging from resisting arrest to conspiring to impede an officer.

The Department of Homeland Security defends the operation, alleging officers face hostile crowds as they pursue violent criminals.

Gregory Bovino, the Border Patrol commander who’s brought controversial tactics from operations in Los Angeles, called Chicago a “very non permissive environment.” He blamed sanctuary protections and elected leaders and defended agents’ actions, which are the subject of lawsuits.

But the operation’s intensity could subside soon.

Bovino told The Associated Press this month that U.S. Customs and Border Protection will target other cities. He didn’t elaborate, but Homeland Security officials confirmed Saturday that an immigration enforcement surge had begun in Charlotte, North Carolina.

DHS, which oversees CBP and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, has said operations won’t end in Chicago.

Interest nationwide

Alonso Zaragoza, with a neighborhood organization in the heavily immigrant Belmont Cragin, has printed hundreds of “No ICE” posters for businesses. Organizers in Oregon and Missouri have asked for advice.

“It’s become a model for other cities,” Zaragoza said. “We’re building leaders in our community who are teaching others.”

The turnout for virtual know-your-rights trainings offered by the pro-democracy group, States at the Core, doubled from 500 to 1,000 over a recent month, drawing participants from New Jersey and Tennessee.

“We train and we let go, and the people of Chicago are the ones who run with it,” said organizer Jill Garvey.

Awaiting the aftermath

Enriquez completes up to three patrol shifts daily. Beyond the physical exertion, the work takes a toll.

Federal agents visited his home and questioned family members. A U.S. citizen relative was handcuffed by agents. His car horn no longer works, which he attributes to overuse.

“This has been very traumatizing,” he said. “It is very scary because you will remember this for the rest of your life.”

By SOPHIA TAREEN and CHRISTINE FERNANDO

Associated Press